Much has been written of the transformation of modern lending markets: in the East, amid the rise of China’s particular financial system (the proliferation of the so-called “shadow banks”) and, in the West, in the wake of the financial crisis, which spurred the growth of so-called “direct lending”. Both of these are flavors of the same phenomenon: lending, once the exclusive domain of traditional, storied banking houses, has been reinvigorated and reformed by the entrance of new lenders.

This transition, the democratization of lenders, is also taking place in the crypto markets in a serious way. Billions of dollars of loans have been channeled to crypto-native borrowers by both traditional and crypto-native lenders via both cash and crypto settlements. The duality here is important.

The business of crypto lending is in truth a mix of disparate transaction patterns which in other, more traditional circumstances would not usually be combined. The situation of a cash lender assessing the systematic and idiosyncratic default probabilities of crypto-native businesses is quite distinct from that of a prime broker offering their trading clients leverage on assets, itself very different from that of an agent who is long BTC lending that collateral out to short sellers for return enhancement. But there is a profitable interpretation of this combination, namely that, because all these facets of the crypto lending business have to face, in some way, the price of Bitcoin, we should consider the incentives, risks, and structures that that common exposure creates.

In this series of notes, we’ll examine a few different types of transactions in order to give a sense for what’s going on in each. In Part I, we’ll discuss what happens in transactions that involve borrowing cash with crypto collateral. Part II will cover lending both cash and crypto as an investment, and Part III will close things out with a look at borrowing crypto against other crypto, which will also allow us to discuss crypto-native financial solutions such as staking and decentralized finance. Hopefully, the combination of these surveys will end up giving a sense for the state of the lending markets at large.

I: Borrowing Cash with Crypto Collateral

We at Wave have always seen the growth of the derivatives markets as one of the most exciting and important developments in crypto, which motivated us in 2019 to launch the first tokenized crypto derivatives-based yield fund in the form of our BTC Income & Growth Digital Fund. One reason for that focus is the incredible volatility of BTC and the altcoins, which we recognize as a feature totally distinct from other financial assets. While high volatility leads to interesting solutions in derivatives trading, it can make proper loan collateralization more difficult.

Still, even at the time, it was recognized that the long-term views of many whales and other large players in crypto would make these transactions attractive despite the steep terms. The increasing centralization of mining for proof-of-work coins, in particular, led naturally to a set of targeted clients for these lenders: the miners themselves, who face accounts payable denominated in cash but earn their revenue in crypto terms.

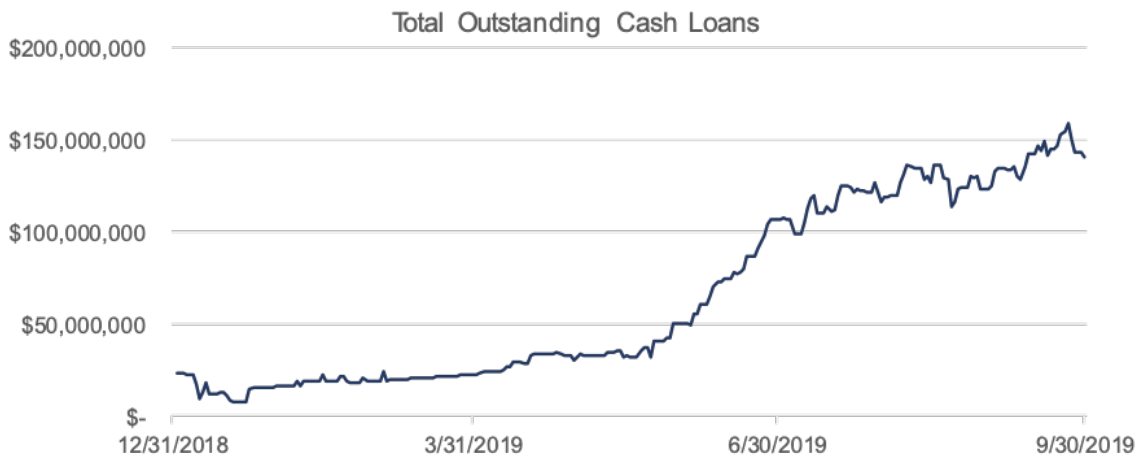

Since then, crypto-collateralized lending has boomed. At the end of 1Q2020, Genesis Capital, the lending arm of New Jersey-based Genesis Trading, noted their USD and equivalents book had more than $230mm in loans outstanding.

For the type of loans we were discussing above, this cash’s destination is usually Asia, particularly China, where many of the biggest mining pools have their operations. However, it turns out that there’s more to the story than miners looking to borrow against their BTC-denominated revenues. Indeed, the greater portion of cash loan demand comes not from people looking to use USD in the real economy, but rather from traders seeking to finance new action. In Genesis’ words, “every time a dollar is borrowed against BTC collateral, the cash is largely used in one of two use cases: speculation or working capital. Speculation is the simplest, where the cash is borrowed to purchase more BTC and leverage long.”

And while they offer precisely the same example of a miner seeking cash to pay electricity bills as the archetypal working capital borrower, in their 4Q2019 note, they state more forcefully that the demand for cash loans “is a function of forward curve steepening (arbitrage opportunity) and desire for leverage among hedge funds and miners” – that is to say, for financing trades.

This kind of transaction does have a traditional antecedent, and it would usually be serviced by prime brokers, big departments at bulge bracket banks engaged in low margin, high balance sheet lending. The diagram below offers an illustration of the relationship between traders like hedge funds and prime brokers.

Prime brokerage is an old business, but it remains so central to the workings of modern finance, in all its heady spiraling nooks and crannies, that understanding its functions helps to clarify much of why things are the way they are. At its core, prime brokerage helps grease the rails of trading and settlement – the business grew up in the equities markets as a way of making sure all the different brokers and traders could get their positions reconciled. They have grown into providing services like custody, portfolio reporting and analytics, and even things as far afield as office planning. More relevant, however, is their role in financing hedge fund portfolios. Leverage is a trick even older than prime brokerage, and every fund employs some variant of borrowing to increase return on equity. For most hedge funds, the place they go to get more cash is their prime broker, precisely in the same way Genesis Trading interacts with its BTC traders. (Truth be told, traditional prime brokers are less frequently the ones putting a balance sheet to work in the service of financing risky hedge funds – instead, they’ll work with the (probably in-house) commercial banking arm.)

Of course, the risks involved in financing a miner’s working capital and a trader’s leverage are distinct, which puts pressure on crypto lenders to be savvy in their underwriting decisions. An informational page on BlockFi’s website puts the point more pithily: “This means, when it comes to interest returns, it very much matters to whom those funds are being lent.” In terms of assessing where the lending market is today in its ability to accurately price such thorny portfolios of borrowers, we would say that the current excess demand for cash by traders allows the market to clear rather high interest rates on these loans, and that, in a sense, the distinction in the risks each borrower brings is swallowed up by the massive spread these lenders are making. This, however, is not a permanent state of affairs, and with a sufficiently large shift in market conditions, we would expect to see lending standards tighten as lenders scrutinize their borrowers more carefully. And if that evolution fails to come about, then perhaps by the continued market entrance of less risk-averse lenders, we could expect to see potential loan defaults as inappropriately priced risk goes the wrong way.

Since we have made reference, at this stage, to the rate of interest these crypto loans bear, it’s worth examining more closely what factors help to shape the lending market. As above, we note that the demand for crypto-collateralized cash loans comes less from agents looking to finance working capital and more from traders seeking to capture price movements opportunistically. Quoting Genesis again, the demand for cash loans “is a function of forward curve steepening (arbitrage opportunity) and desire for leverage among hedge funds and miners”. The desire for leverage is a variable that’s pretty hard to pin down – we would only note that, anecdotally, some traders look to the level of open interest in BitMEX’s XBTUSD perpetual swap as a sign of market exuberance, reflecting as it does probably the easiest way to get leverage in the spot BTC. The influence of the shape of the forward curve, however, is easier to explain.

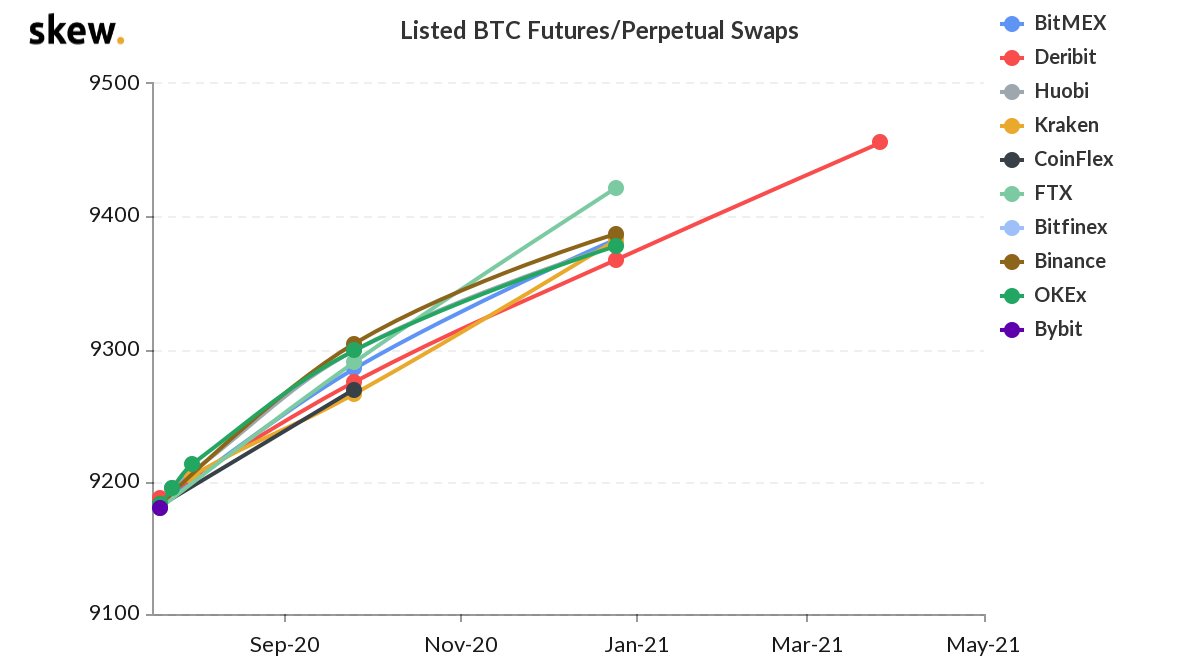

Recall that the price of a futures contract will tend to differ from the spot price of the underlying asset it references. This difference is determined at minimum by the degree of opportunity cost and the cost of storage, but in most markets moreso by future expectations for supply and demand. (This is unimportant, but the words are fun, so we’ll remind you that when the futures price is above the spot price, the curve is in contango, and when otherwise, in backwardation.) At the time of writing, the forward BTC curve was in contango, as it usually is.

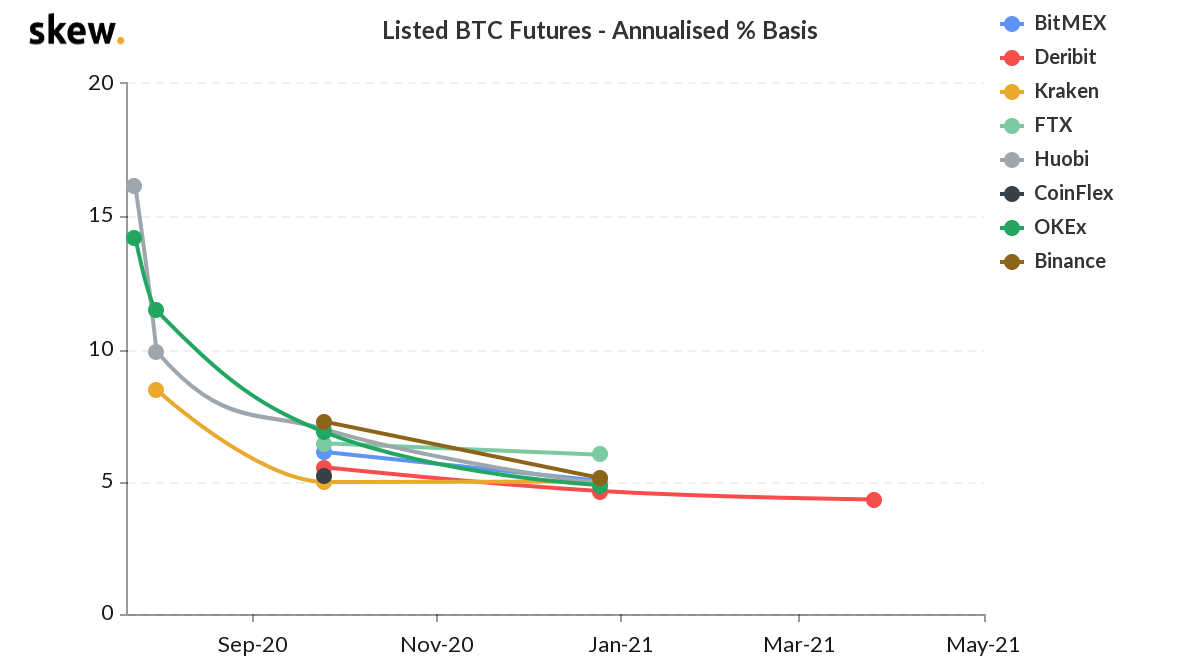

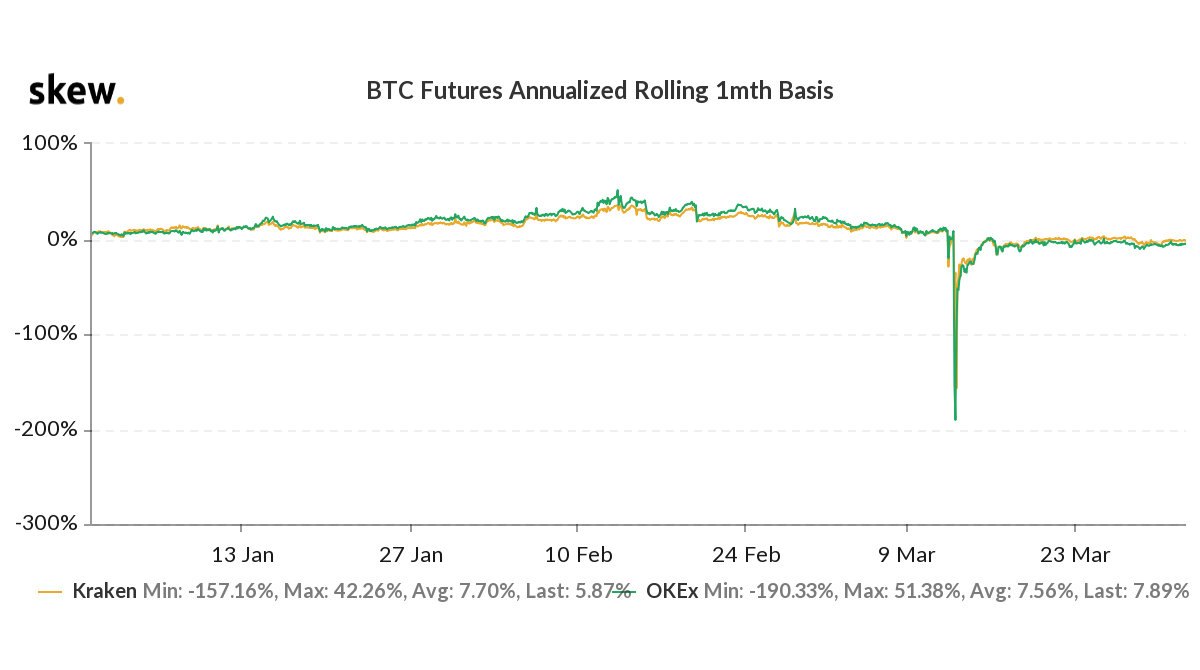

You can also describe this relationship by taking the annualized percentage difference in spot and future price for each contract to build a curve of the basis.

Traders like to think of the forward curve in this way because it captures succinctly the return earned by entering into so-called cash-and-carry trades. A trader who owns an underlying asset and sells a futures contract referencing that asset has no economic exposure to the asset over the life of the futures contract. They capture the basis between the prices at the time they sell the futures contract and are immunized from changes, up or down, in the spot price as time passes to the expiry of the futures. When that basis is sufficiently high, this trade, the cash-and-carry, can be quite attractive.

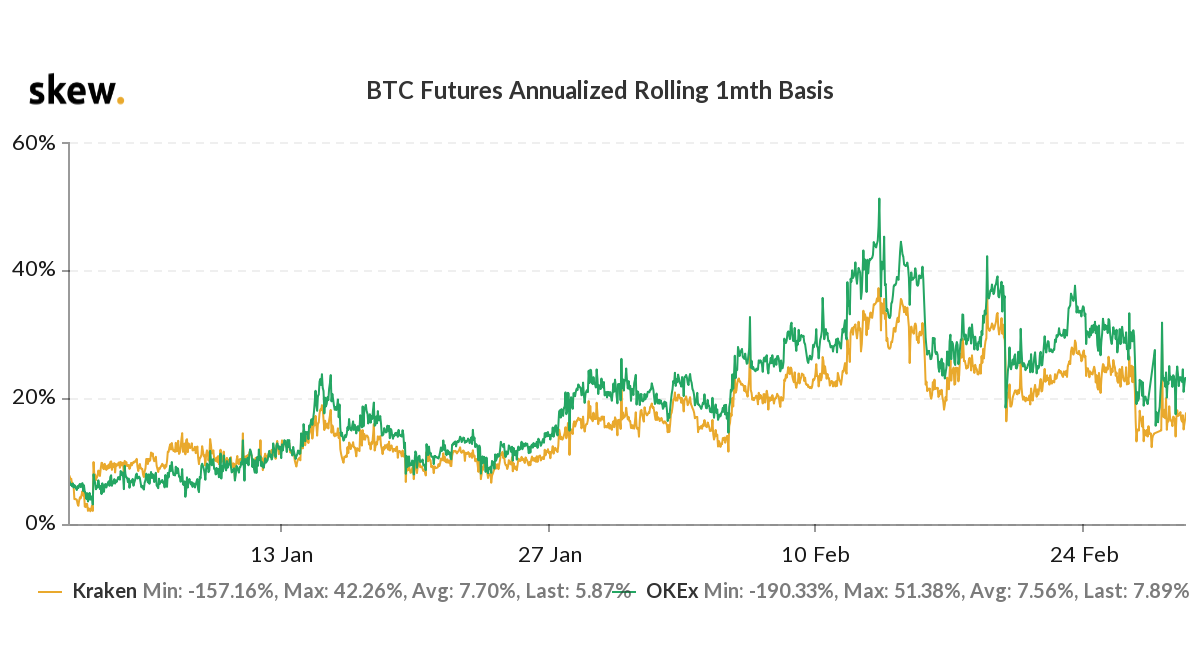

Right now, for example, a trader earns 5-7% by entering a cash-and-carry trade out to the Sep 24th contract, depending on the platform they use. In February of this year, the cash and carry became exorbitantly profitable: traders were able to obtain, however briefly, a 50% return for one month’s trade.

This particular period is a good example of why the cash-and-carry is a useful tool for ensuring the smooth functioning of futures markets. Such an incredible premium incentivizes traders to enter the trade, selling the futures, buying spot BTC, and therefore compressing the basis. It’s here that lending reenters the picture.

Imagine a trader who wants to enter into a cash-and-carry trade but has neither assets nor cash (we can all imagine such a particular someone). What does he do? Well, he can start off by selling the futures contract short – this costs essentially nothing, but it also doesn’t raise any cash he can use to finance the long position. How will he get long the underlying? He’ll have to go into the lending markets and borrow the cash he needs to buy the asset. The rate the lender charges him on that loan will depend, among other things, on the level of collateralization agreed to. This lending relationship constrains him in an important way – no matter the level of the basis present in the futures market, he can only enter the trade profitably if the basis he captures is greater than the rate of interest he pays over the same period. This, then, is a second well-designed market feedback loop: as the basis rises exogenously, traders will borrow cash to finance cash-and-carry trades, which will close the basis but also bid up the interest rate on cash borrowing, which will reduce the attractiveness of entering the trade to new traders, helping the market to reach an equilibrium. This applies both to fictional asset-free traders like the one we imagined as well as real-world, well-capitalized actors, because everyone is facing – sometimes internally and invisibly – the same constraints.

We have refrained from referring to these traders who play in the futures markets in this way as arbitrageurs because it is hard to describe the cash-and-carry trade as true arbitrage. The history of the financial markets is riddled with car crashes of traders headstrong enough to convince themselves of the persistence of a particular level of basis. By way of illustration, let’s examine that annualized rolling 1mo basis if we extend the end date out to Apr 1st.

The mouth-watering 50% premium present in February we discussed above is scarcely a blip once the effects of the mid-March drop are accounted for. If you were implementing a cash-and-carry strategy in your fund on the assumption that the basis “never went away,” you would be quite sore about it come roll day. Of course, this is finance, and so merely by undertaking transactions opposite to those we described – which would mean going long the future and short the spot – you could have made money all the same.

Tradersdna is a leading digital and social media platform for traders and investors. Tradersdna offers premiere resources for trading and investing education, digital resources for personal finance, market analysis and free trading guides. More about TradersDNA Features: What Does It Take to Become an Aggressive Trader? | Everything You Need to Know About White Label Trading Software | Advantages of Automated Forex Trading