There are a couple of good reasons as to why so-called dollar hegemony may be on the wane. One is the relative rise of other economies, notably China and India. Another is the deterioration of US finances. The US budget deficit is expected to deteriorate in the coming decades and taking steps to address that will be challenging, given the poisonous political environment.

Over the past couple of months, there’s been a lot of discussion about the end of the dominance of the US dollar in global trade and finance. That dominance has been a source of influence for the US over the global financial system, global monetary policy and geopolitics.

There are a couple of good reasons as to why so-called dollar hegemony may be on the wane. One is the relative rise of other economies, notably China and India. At the recent BRICS conference in Johannesburg there were calls for the BRICS countries to create a common currency specifically to reduce their dependence on the dollar. Another is the deterioration of US finances. The US budget deficit is expected to deteriorate in the coming decades and taking steps to address that will be challenging, given the poisonous political environment.

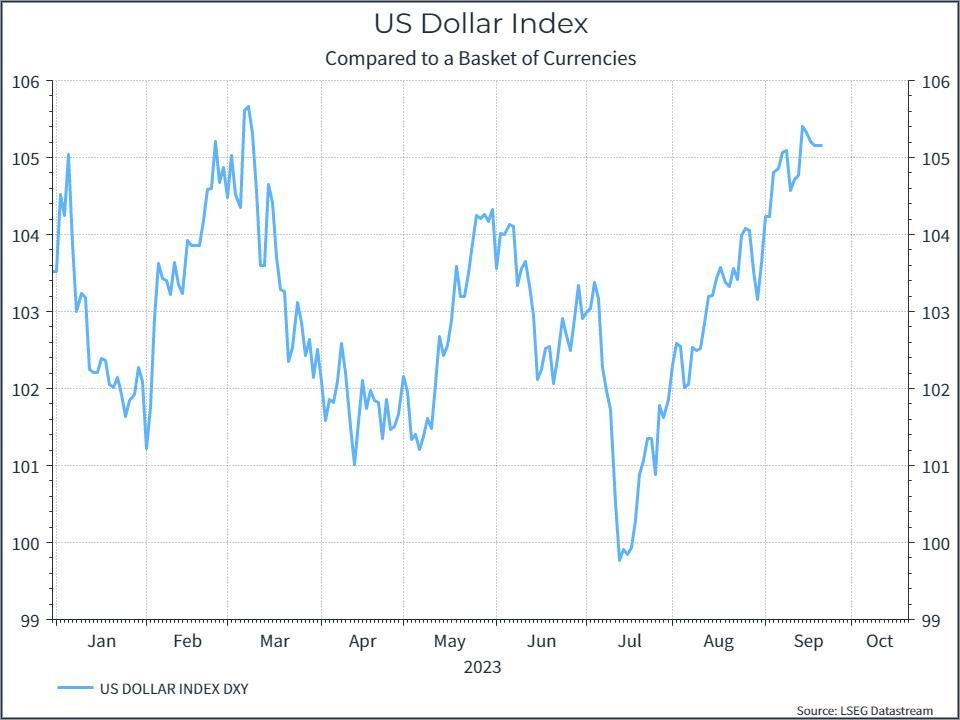

As is often the way, all the articles over the summer about the end of dollar dominance coincided with a rally in the dollar relative to other major currencies, as the chart below indicates. And that’s an important lesson. Analysts have been calling for the “demise” of the dollar for many years. There’ve usually been some good arguments for it, but it hasn’t happened yet.

But let’s take a step back. What does the role of the dollar as a reserve currency mean from a portfolio perspective? We’ll look at three possible impacts. First, you could argue that it has allowed the US Treasury to issue debt at a lower interest rate than might otherwise have been the case. Second, it might mean that the dollar has been consistently stronger relative to other currencies than it ‘should’ have been – based on economic metrics. Third, you could also argue that having a dominant currency to price things like commodities provided some efficiency benefits for global trade.

If we were to see the dollar lose that status – would we then see those trends reverse? In other words, could we see US Treasury yields be higher compared to history on a sustained basis? Would we see the dollar weaken? And could we see more friction in global trade?

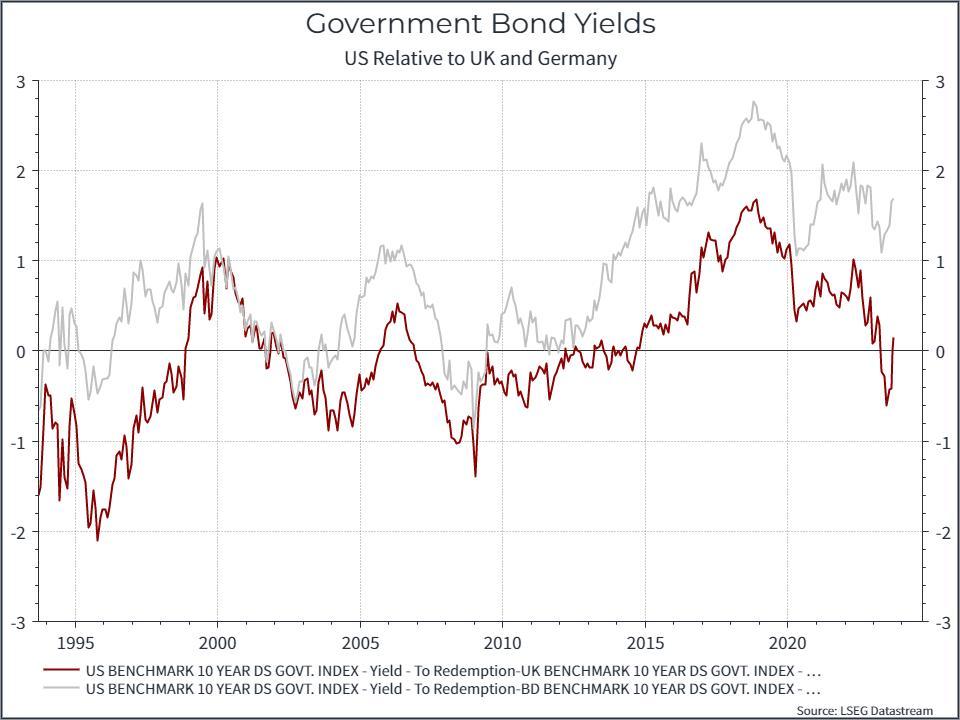

The charts below address some of these points. The first shows US government bond yields compared to Germany and the UK. It’s a pretty crude comparison, given inflation and currency differences, but US nominal yields have generally been above both Germany and the UK in recent years – so maybe the benefits in terms of lower yields aren’t so clear. Nonetheless, If US government bond yields were to rise further on a sustained basis, it would likely have a negative impact on other asset classes.

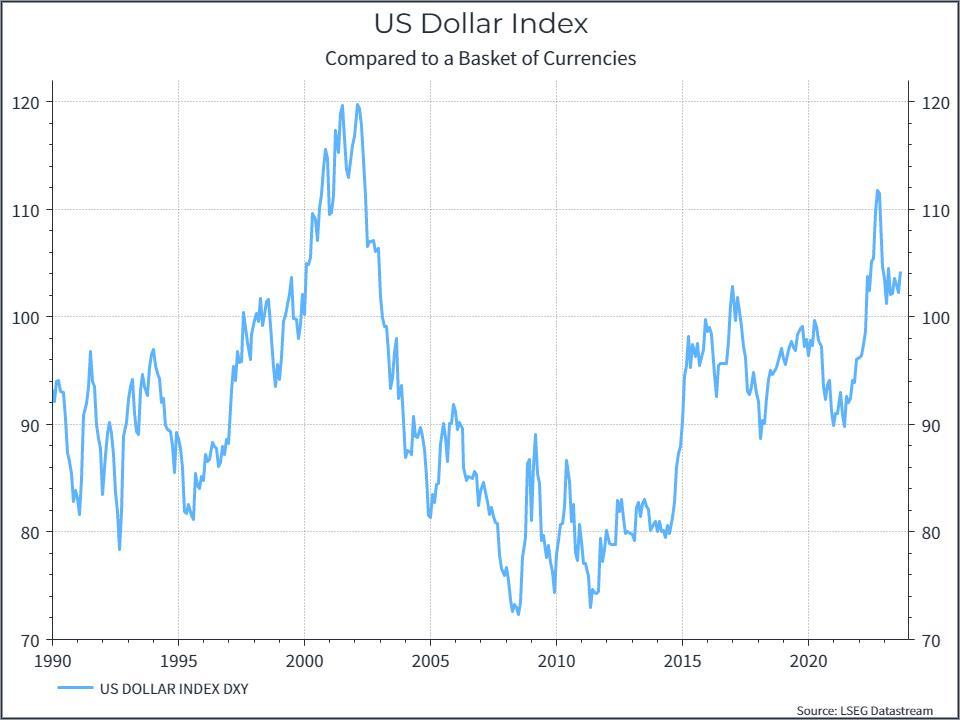

The next chart shows US dollar index, which measures the dollar against a broad range of currencies. As we can see the dollar has moved around a lot over the years. There hasn’t been a steady appreciation that the proponents of dollar hegemony might suggest. The counter argument here is that in real terms (ie adjusting for inflation) the US dollar does look more

The situation is made more complex by possible interaction between these two variables. If we did see higher US government bond yields, that could prompt the dollar to strengthen rather than weaken.

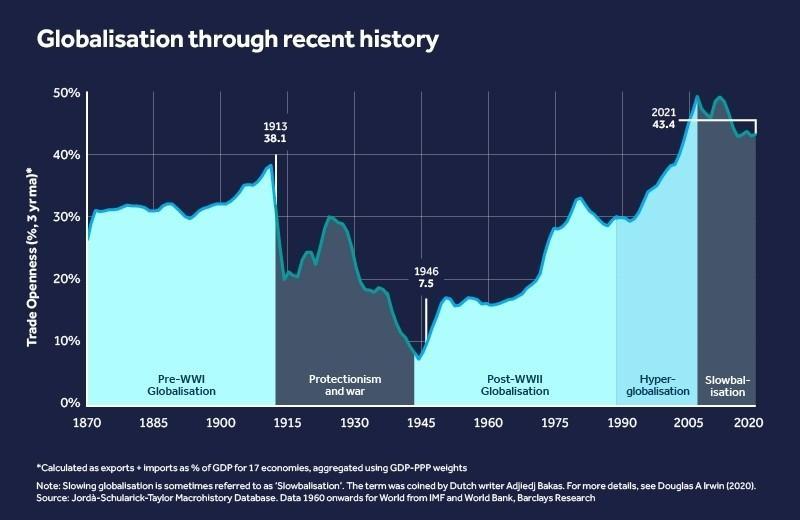

Finally, the point around potential trade frictions is interesting. We’d argue that there could be efficiency benefits from having a relatively dominant currency. The greatest benefits flows to the US, but other countries could gain as well. If we were to see more fragmentation, and many argue that’s already begun to happen, and it could be a reflection of a more uncertain world.

As to where we are today, the chart below gives a long-term perspective on globalisation – in terms of trade flows. It suggests that we’re in a period of relative stagnation – where globalisation hasn’t continued to gain ground but hasn’t yet turned down. In this case, a fragmentation of the global financial system might exacerbate a trend that we may already be beginning to see.

Where does this get us? The US faces significant challenges, but its economy remains relatively robust and its pre-eminent position in the global financial system doesn’t look under imminent threat. Even if we did see a rebalancing of global financial influence, we’d still expect the US to remain the largest capital market globally for the foreseeable future.

If we did see a rebalancing of global financial influence, you might see that reflected in US bond yields, the currency and global trade. But recent history doesn’t paint a clear picture. US Treasury yields (in very crude terms) don’t look especially low compared to, say, Germany or the UK. The US dollar hasn’t seen uninterrupted appreciation against major currencies and global trade has already hit a bit of a wall. It may be too soon to call time on the dollar, but maybe we’ve already seen some of its impact.

The article is by Richard Flax, Chief Investment Officer, Moneyfarm.

Read More:

no income verification personal loans

crypto mining tools crypto premier guide

plataforma iphone de trading en forex

no income verification personal loans

Tradersdna is a leading digital and social media platform for traders and investors. Tradersdna offers premiere resources for trading and investing education, digital resources for personal finance, market analysis and free trading guides. More about TradersDNA Features: What Does It Take to Become an Aggressive Trader? | Everything You Need to Know About White Label Trading Software | Advantages of Automated Forex Trading