By Nikki Howes, Investment Associate at Heartwood Investment Management, the asset management arm of Handelsbanken in the UK

On 1 November, former IMF chief Christine Lagarde was handed the baton by Mario Draghi to become president of the European Central Bank (ECB). Lagarde is joining the ECB at a time when the European economy is losing momentum, and her appointment has been criticised in some circles as she lacks economic experience. However, it has also been suggested that not coming from an economic background may mean she is more open minded, particularly given her experience on the international stage.

Lagarde joins from the IMF, having been appointed managing director in 2012, following a stint as the first female finance minister of France between 2007 and 2012. Previously, she was a lawyer at Baker McKenzie from 1981, becoming the company’s first female chairman in 1999. During her time at the IMF, she focused on rebuilding the institution’s credibility, and although Greece’s 2010 bailout and the IMF’s biggest bailout (a $57bn deal for Argentina in 2018) were seen as controversial decisions, her diplomatic and negotiating skills were highly applauded.

What kind of ECB is Lagarde inheriting?

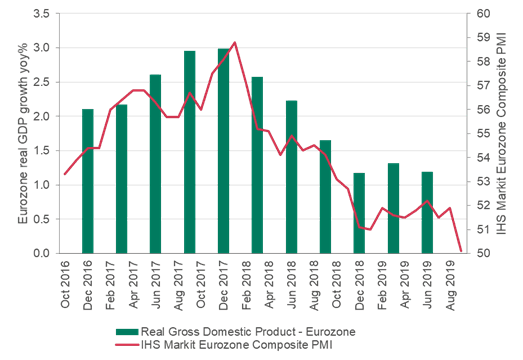

At the ECB, Lagarde takes over from Mario Draghi, who has recently presided over a raft of monetary stimulus measures within an environment of weak economic growth and low inflation. Germany’s economy in particular has shown intensifying weakness with business indicators suggesting a deterioration in manufacturing, services and job creation; the detrimental impact of global trade tensions have hit export-dependent industries in the country especially hard.

In Draghi’s penultimate ECB meeting in September, he clearly set out the future path for Lagarde with an ambitious monetary stimulus package. This included a cut in the bank deposit rate to -0.5% and the reinstatement of the Governing Council’s asset purchase programme (in essence a bond buying programme, also known as quantitative easing (QE)) from 1 November, with purchases worth €20 billion a month for as long as they are required. This was significant as it means asset purchases are now open-ended, dubbed by many as ‘QE infinity’, signalling central bank support is here to stay. Draghi also introduced a tiering system for interest rates on excess bank reserves and made amendments to the terms of the third round of Targeted Longer Term Refinancing Operations (known as TLTRO III), a favourable lending programme for banks designed to encourage lending into the real economy. These latter policy moves were specifically aimed at providing support to the banking sector, which has been feeling the pressure from negative interest rates.

However, not all ECB Governing Council members were on board with the policy package. Several of the 25 members are believed to have opposed the interest rate cut and the resumption of bond buying and one member of the ECB’s Executive Board resigned. Lagarde is inheriting a deeply divided council.

Against this backdrop, what choices does Lagarde have?

Lagarde has so far supported Draghi’s position on monetary policy and her diplomatic skills may be needed to get the dissenting council members on side. She has also urged a reform of Europe’s budget rules, calling for changes that would incentivise member countries to save more in the good times for use in the bad. There is already a broad debate in Europe over the role of fiscal (rather than purely central bank) policy in countering slow growth and potential recessions as the leading economies lose momentum. There are worries too that central banks’ ability to battle recessions has been diminished by the current low interest rate environment and that fiscal policy will therefore need to play a bigger role. Lagarde needs to energise a sluggish eurozone economy in which inflation stubbornly lags well below the ECB’s target of close to 2%. In a persistent low inflation rate environment, traditional central bank tools may be inadequate. That has certainly been the experience of Japan, where even extraordinary monetary policy measures, including buying equities, have struggled to generate inflation.

What’s more, government spending policies ought to be highly effective at the moment. With sovereign borrowing costs so low, and likely to stay that way for the foreseeable future, a policy of well-designed fiscal support should be seen favourably by member states, particularly those such as Germany with plenty of fiscal headroom. However, Germany is committed to a balanced budget approach to its finances and although it has recently announced some small stimulus measures in the form of green initiatives, it remains resolutely committed to its black zero target.

Once again Lagarde’s diplomatic and negotiating skills may be called upon to advance the case for fiscal policy in enhancing the effectiveness of central bank support.

What may come next?

In the chair for her first ECB monetary policy meeting, Lagarde is not expected to make any immediate changes to the current policy settings. She is however, expected to launch a strategic review of the ECB’s tools and objectives, a move likely to help start bridging the current divide in the Governing Council.

As she begins her eight-year presidency of the ECB, the hope now is that Christine Lagarde – with her mix of interpersonal skills, professional networks, and national and international policy experience – will prove to be the catalyst to kick-start the recovery that Europe needs.

Read More:

how to handle online loan harassment

draw regrassion channel indicator for mt4

bulls and bears indicator fot mt4

Tradersdna is a leading digital and social media platform for traders and investors. Tradersdna offers premiere resources for trading and investing education, digital resources for personal finance, market analysis and free trading guides. More about TradersDNA Features: What Does It Take to Become an Aggressive Trader? | Everything You Need to Know About White Label Trading Software | Advantages of Automated Forex Trading