By Donald A. Steinbrugge, CFA – Founder and CEO, Agecroft Partners

Globally coordinated monetary stimulus prevented a potential economic meltdown in 2008 and helped create a quick rebound in the capital markets. We have since seen the longest economic expansion on record. Unfortunately, the effectiveness of monetary stimulus declines the more it is used. Ideally, it should only be used during recessions in order to reduce a downturn’s severity and duration.

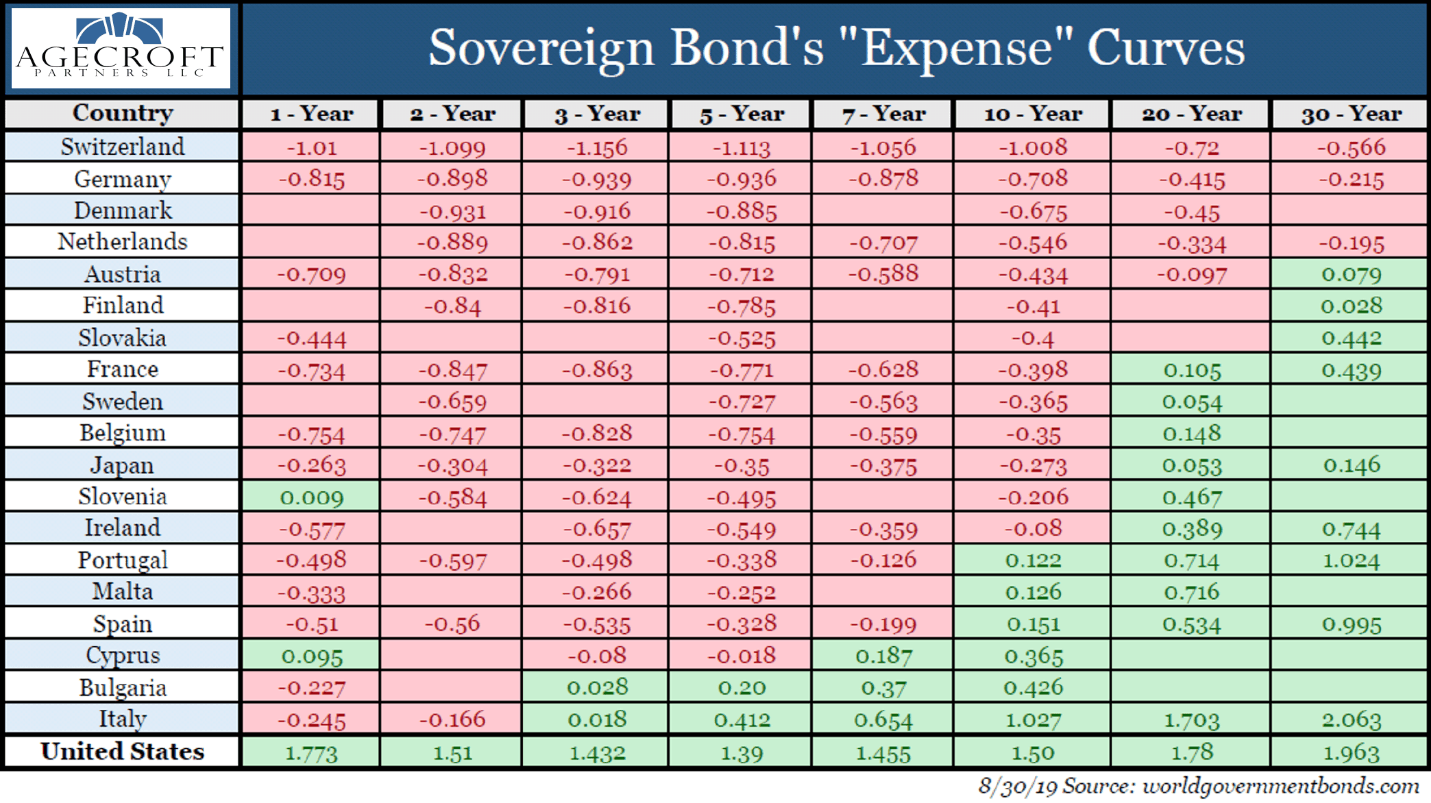

Recessions are a natural occurrence in an economic cycle. They are unpleasant when they occur, but can be helpful to the economy in the long term. Recessions drive out inefficient companies and capital is recycled into growing parts of the economy. The longer recessions are artificially delayed, the more severe they may ultimately become. Unfortunately, many governments have over used monetary policy, creating approximately $17 trillion of sovereign debt yielding a negative interest rate. This can be easily conceptualized by viewing the chart below, where we have substituted the word yield with the more appropriate word, expense.

Not only is monetary easing now having little impact in stimulating these economies, but it is significantly increasing the potential severity of a future recession. Overuse has effectively eliminated one of the major tools available to simulate the economy.

How much lower can governments reduce interest rates that are already negative? Many point to Japan as an example of a country that has been able to operate in a low interest rate environment for a very long time. However, Japan may not be an appropriate comparison. Japan benefited from a growing, globally integrated world economy being driven by many other countries. The economic landscape has shifted. Today, there are very few “other counties” left with sufficient dry powder to stimulate their economies.

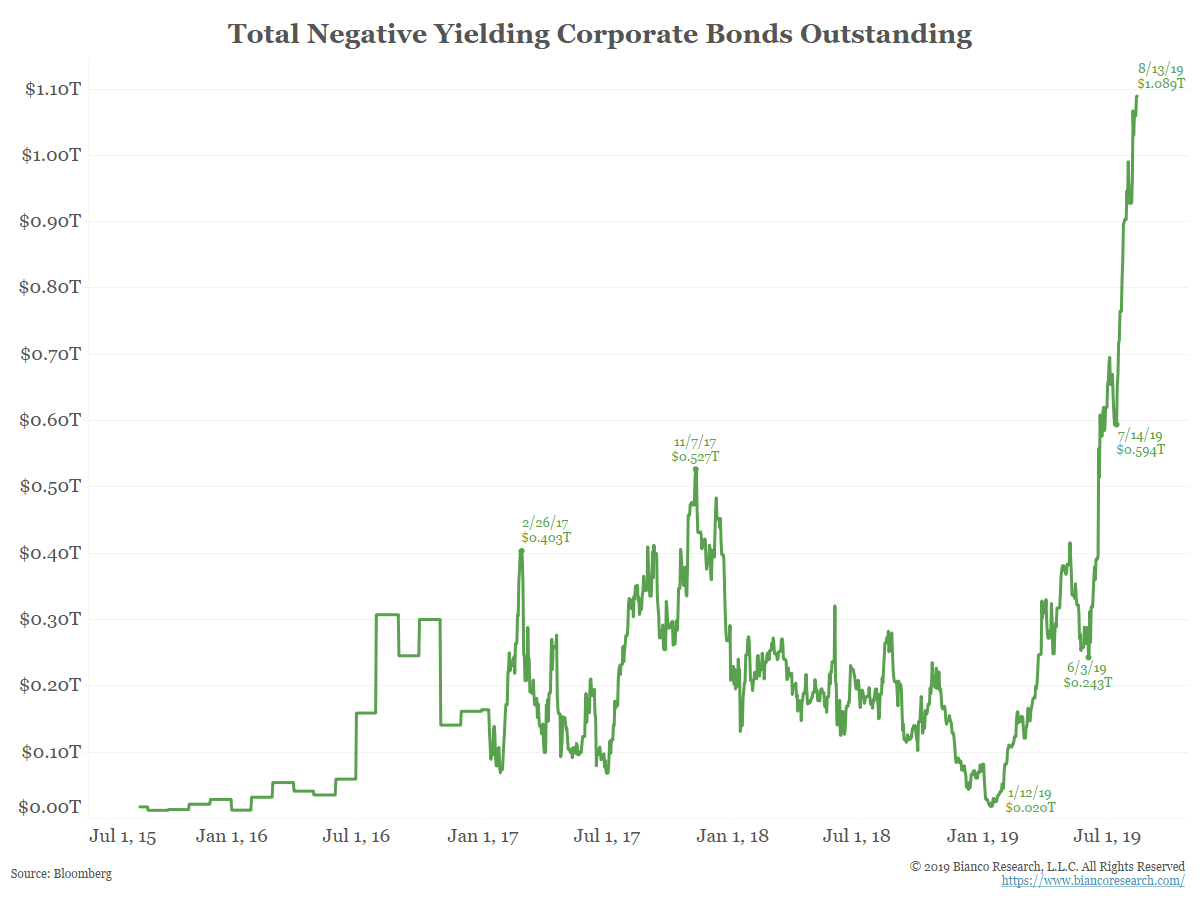

Negative interest rates are not just confined to sovereign debt. Corporate debt outstanding with negative yields surpassed $1 trillion in August.

What are the short term effects of negative interest rates?

1. Banks have had a very difficult time making money in this environment. They have been reluctant to pass negative rates to their retail customers. As their net interest margins deteriorate, it makes it more difficult for them to lend and withstand a major correction in the economy. The Euro Stoxx Bank index is down 22.5% over the past 12 months. It currently stands at 86, down from its all-time peak of 485 reached in May 2007.

2. Low and negative rates artificially inflate equity valuations through price earnings ratio expansion instead of earnings growth. Fixed income market performance has also been enhanced by capital gains from decreasing yields. A large portion of these gains could be reversed if interest rates rise.

3. Low yields on fixed income and high price earnings multiples for equities reduce forward looking expected returns across all asset classes. This disproportionately hurts retirees who are more likely to have a large percentage allocated to fixed income and had expected to live off interest payments. They may now be forced to spend down their principal to generate sufficient cash flow.

4. Negative rates increase the unfunded liability for both corporate and public defined benefit pension plans. This increases the probability that some plans will become insolvent and not pay out all benefit obligations.

5. Monetary easing into negative rates can fuel a decline in corporate and consumer confidence in the outlook for the economy. This will first be seen in a reduction of capital expenditures by companies, which has already begun. It can eventually lead to a drop off in consumer spending. Once this confidence is lost GDP will contract and it will be very difficult to reverse.

6. Negative interest rates are having very little impact on economic growth, but should reduce the value of local currency and increase the competitiveness of exports. Unfortunately, this can also lead to currency wars.

7. Increase probability of a major recession and market selloff with an increase in correlations between asset classes.

What happens if we have another 2008?

Governments have three primary options to stimulate their economies.

1. Monetary policy of lowering interest rates

Due to over use and with rates near zero or negative, this option’s effectiveness has been significantly reduced.

2. Monetary policy of purchasing securities

This historically has had two benefits: reducing interest rates further out the yield curve and increasing the money supply. With 10 year rates near all-time lows, there is not a lot of room to go lower. In addition, as the capital markets become more globally integrated, foreign investors are reducing the government’s ability to influence their domestic yield curve. Increasing the money supply requires a very delicate balance. If governments provide too much liquidity, inflation could come roaring back. This might be difficult to control leading to stagflation.

3.Fiscal stimulus

Large infrastructure projects are one example of ways deficit spending can be used to boost employment. Unfortunately, this fiscal stimulus would be on top already massive deficit spending which is expected to significantly increase over time to pay for social welfare benefits for aging populations in developed economies. For example, the US federal debt is $22 trillion. The estimated unfunded liabilities of Social Security, Medicare and Medicare add another $50 Trillion. Many believe that government deficits do not matter, especially in your own currency. Politicians running for office are “one-upping” each other by promising to give away more benefits if elected. The truth is that deficits growing too quickly and too large are a ticking time bomb. They can be supported as long as people have faith they will get their money back. If that faith is lost it can end very badly.

How bad could it get?

The best way to answer this question is by visualizing a distribution curve of possible outcomes with the potential for large tail risk. Many people are concerned that negative sloping yield curves, trade wars and Brexit could all lead to slower GDP growth and even a recession. Negative yields combined with massive government deficits and unfunded social welfare programs have the potential to greatly amplify both the severity and duration of an economic recession and a decline in the capital markets.

A worst case scenario could play out if contracting European economies are met with aggressive monetary and fiscal stimulus that have little impact in reviving the economy. At first, equity markets would begin to sell off, further hurting consumer confidence. Eventually, the aggressive monetary and fiscal stimulus would create an inflationary environment creating stagflation – rising prices in a contracting economy. This could cause interest rates to skyrocket and, in turn, bond and equity values to plummet. This would lead to wide-spread bank failures and very high rates of unemployment. It would also put significant strains on governments’ balance sheets as interest rate expense on government debt would increase multiple times. Simultaneously, this environment could slowly begin to spread to the US, Asia and other parts of the world. Eventually, it could lead to political unrest and the destabilizations of some governments.

Events of the past couple of decades have led investors to expect markets to rebound quickly from a major correction. Seemingly forgotten is the worst sell-off of the US stock market, which began in 1929 and resulted in a decline of almost 90 percent. It took 23 years to recover. For those tempted to dismiss this as outdated data, take note that the Nikkei index hit an all-time high of approximately 39,000 in 1989. 28 years later it is still approximately 40 percent below its peak.

About the author

Donald A. Steinbrugge is the Founder and CEO of Agecroft Partners, a global hedge fund consulting and marketing firm. Agecroft Partners has won 36 industry awards as the Hedge Fund Marketing Firm of the Year. Don frequently writes white papers on trends he sees in the hedge fund industry, has spoken at over 100 hedge fund conferences, has been quoted in hundreds of articles relative to the hedge fund industry and has done over 100 interviews on business television and radio.

Tradersdna is a leading digital and social media platform for traders and investors. Tradersdna offers premiere resources for trading and investing education, digital resources for personal finance, market analysis and free trading guides. More about TradersDNA Features: What Does It Take to Become an Aggressive Trader? | Everything You Need to Know About White Label Trading Software | Advantages of Automated Forex Trading